07 March 2012 |

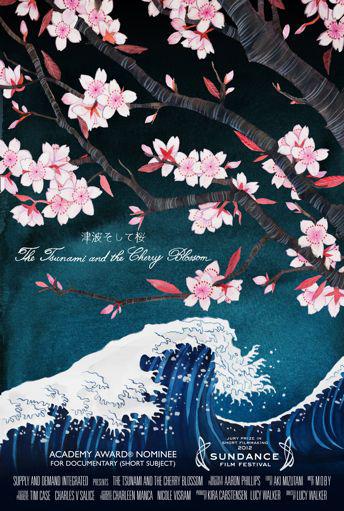

The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom is a film directed by British director Lucy Walker that was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Short Documentary, and won the Sundance Jury Award for Non-Fiction this year. The film is described as "A stunning visual poem about the ephemeral nature of life and the healing power of Japan¡Çs most beloved flower."

With a keen interest in photographing blossoms since her teens, Lucy only realised that her passion was shared by an entire nation when she visited Japan for the first time - witnessing how people dropped everything for "hanami parties" and eagerness with which the "sakura zensen" (the blossom progression front) was followed. |

|

However, in more recent years her memories associated with the blossoms are more poignant as they are tied in with her experience of taking care of her mother who was ill with cancer. She notes that since the passing of her mother (and shortly after, her father as well) she wanted to make a film about cherry blossom, to ask how human beings can find hope after loss, and how to carry on given the suffering and shortness of life. "I've wanted to go to hanami (cherry blossom viewing parties) and read haiku and drink sake and get high on life and talk openly about death."

Lucy was scheduled to promote her latest film Countdown to Zero in Japan when the worst earthquake to ever hit Japan struck on 11 March. With the release of the film postponed, there was no need for her to travel to Japan at all. But she recalls that she "couldn't help thinking that maybe this was the most important time of all to go to Japan, to express our solidarity with the survivors, and to witness this cherry blossom season - with its spirit of renewal, and its symbolism of the fragility of life."

She talks about her subsequent visit to Japan and how the film The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom came to be made.

"When we landed in Tokyo the immigration officers at the airport were very surprised to see us, since the foreigners were all departing. Even in Tokyo there were rolling blackouts, radiation contamination alerts, and the shelves were empty of bottled water and drinks. It wasn¡Çt easy to reach the north-eastern Tohoku region devastated by the tsunami - you couldn¡Çt rent a car, the trains weren¡Çt running, but eventually we made it.

|

|

Nothing prepared us for being in the post-tsunami landscape. The damage was unimaginably bad and widespread, stretching for miles in every direction, and there were only very occasionally other lone human beings climbing around over the debris in this post-apocalyptic dystopia. But to my surprise people would approach us, wanting to talk and share their story. And they would spontaneously start talking about cherry blossom, which was starting to bud.

I didn¡Çt have to impose the subject, it was a natural part of everyone¡Çs discussion about how they felt. Everyone had their own view, but many people saw that if the blossom could keep going, then they must do too. That was the best part.

|

There is a Japanese concept of "wabi-sabi" which I love and is at the core of my aesthetic practice, and especially in making this film. I thought it was imperative that this film should be wabi-sabi. A bit simple. Personal, direct, humble, not too slick or fancy or over-the-top. An aesthetic based on transience and modesty, a beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete", with characteristics that include asymmetry, asperity (roughness or irregularity), simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy, and appreciation of the ingenuous integrity of natural objects and processes.

Another Japanese concept which I've thought about a lot is "mono no aware", meaning something like "the pathos of things", "an empathy toward things", "a sensitivity to ephemera", and is a term used to describe awareness of impermanence and the transience of things, and a gentle sadness (or wistfulness) at their passing. Awareness of the transience of all things heightens appreciation of their beauty, and evokes a gentle sadness at their passing, and is associated with Japanese cultural tradition including sakura. |

We were extremely fortunate to be granted an unprecedented interview with Sano Toemon XVI, the sixteenth generation "keeper of the cherries" or "cherry master", whose personal nursery outside Kyoto was perhaps the most beautiful place we had ever visited. As Mr. Sano explains, Buddhism and Shinto meet in Japanese culture, and that meeting is expressed perfectly by the cherry blossom.

As followers of Shinto -- which holds that gods dwell in every feature of the natural world, from tall old trees to sacred mountain rocks -- the Japanese have revered nature since ancient times. Then from the continent came Buddhism and the notion that all things are in flux and nothing is permanent. Eventually the two belief systems fused and spread through the population, giving rise to a spiritual acceptance and appreciation of the constantly changing and regenerating natural world as it is, in all its glory and evanescence.

This philosophy still applies today whenever we encounter cherry blossom. Cherry trees bloom throughout Japan in a single burst of color, flowering in a fleeting beauty, and are shed as quickly as they emerged. In the blossom the Japanese sense impermanence, and in its limited life, they perceive the unlimited beauty of nature. This very sensitivity is part of the culture.

Our goal is that the film will be shared in positive ways to promote understanding, healing, and positive action. Our website www.thetsunamiandthecherryblossom.com has more details.

|

|

Although I had non-Japanese audiences in mind when I was making the film, nothing makes us happier than hearing from Japanese audiences that they have found the film meaningful. My wish is that the tradition of ¡Èhanami¡É cherry blossom vieiwing parties catches on around the world." |

JICC

All quotes are taken from Lucy Walker¡Çs Notes on making the film ¡ÈThe Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom¡É with her consent.

Images: Lucy Walker

|

|