A worldwide movement |

||

|

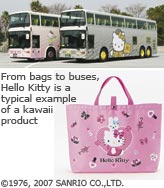

Nowadays, the term °»manga°… is used worldwide to refer to Japanese cartoons, as distinct from American comics or French bandes dessinees. Likewise, the term °»anime°… refers to Japan-produced animation as opposed to Disney cartoons or animation produced elsewhere. The 1990s saw the Japanese animated films AKIRA and Ghost in the Shell become popular among young people in North America, Europe and Asia, but it was also a period during which children and young people began to perceive Japanese pop culture as °»cool°…. In 2003, Spirited Away, directed by Hayao Miyazaki, won an Academy Award for best animated feature film. Moreover, Pokemon, the animated TV programme immensely popular among children, was shown in over 68 countries around the world, further enhancing its appeal. In consequence, the Pokemon market grew to 3 trillion yen in size (about US$250 billion), of which 2 trillion yen was from overseas sales. The Japanese manufacturer Nintendo became a byword for home game machines, while shipments of the PlayStation and PS2, made by Sony Computer Entertainment, reached 100 million units each. Japanese pop culture, which includes manga, anime and games, and the market for them, clearly has the power to transcend national borders, languages and religious differences. |

|

Manga for everyone |

||

|

The foundations of modern Japanese manga and anime were first laid in 1959, with the simultaneous publication of such comics for young people as Shukan Shonen Magajin (Boys°« Weekly) and Shukan Shonen Sande (Boys°« Sunday Weekly) , and then in 1963 with the commencement of TV broadcasting of productions such as the animated series Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) by the cartoonist Osamu Tezuka and Tetsujin 28-go (Gigantor), which was based on an original script by cartoonist Mitsuteru Yokoyama. Since then, the intimate relationship between manga and anime has continued, and even today over 60% of the animated cartoons produced are based on manga, with the cartoonists, manga publishers, animation production companies and the TV stations all in commercial partnership. |

|

Media cross-fertilisation |

||

|

In the animation market, creations such as Space Battleship Yamato and Mobile Suit Gundam appeared in the 1970s and evolved into a variety of forms, from TV animation to film, music and character-based products. This then led to the establishment of a market for toys given away as °»freebies°… with candy and plastic versions of favourite characters. Then in 1983, with the coming to market of the first home game machines, games themselves started to generate their own manga, anime, card game and character-product spin-offs in a kind of media cross-fertilisation. |

|

Expanding markets |

||

|

The impact of Japanese pop culture on the world is not confined just to the economy, the industry or the consumer markets. An even greater influence is exerted on the culture of its fans, the otaku (geeks or nerds, originally a term used to describe young people who stayed indoors reading comics or devoting their time to non-sporting hobbies), the comic market organisers and the fans who dress up in the costumes of their favourite characters. Fans passionate about manga and anime (the otaku) who emerged in the 1970s moved on from a specialised consumer culture collecting comics,

animation software, music software and character goods to the formation of a fully-fledged community. In the manga field, amateur artists started to organise enthusiasts°« buy-and-sell events

on a nationwide scale. The most representative of this trend, the comic market, started such an event in 1975 and it is currently held twice a year. It is now the biggest indoor pay-to-enter event in

the world, with an average of 400,000 visitors every time. |

|

Global mass culture |

||

|

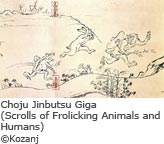

It is sometimes said that the Japanese culture of manga, anime and games is simply a continuation

of a tradition beginning with religious illustrated scrolls such as the Choju Jinbutsu Giga (Scrolls of

Frolicking Animals and Humans) drawn in the 12th century and the ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) of the Edo period. However, the immediate roots of Japanese pop culture can be traced to the importation of overseas comics and animation after the period of modernisation in the late 19th century onwards, and particularly the period of the industrialisation of the anime and manga industry under the influence of the USA after WWII. This fact shows that cultures which transcend borders, languages and religions are the embodiment of a universal trend born out of contact with foreign cultures, much as globally influential impressionist art gained great inspiration from Japanese ukiyo-e. |

|

Text by Megumi Onouchi (Media Content Producer)Copyright 2007 - Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan |