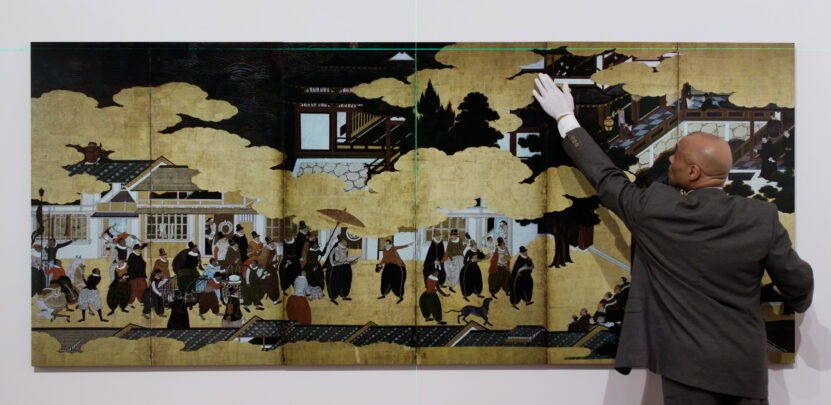

Hikaru Fujii, Southern Barbarian Screens (stills), 2017, single-channel video, 14 min. Courtesy of the artist

Lines, Gazes, Landscapes by Hikaru Fujii

- 5 March - 18 May 2026

- Monday–Friday 9:30 am–5:00 pm (except public holidays)

- Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation, 13/14 Cornwall Terrace, Outer Circle (entrance facing Regent's Park), London NW1 4QP

- https://dajf.org.uk/exhibitions/lines-gazes-landscapes

- +44 (0)20 7486 4348

- events@dajf.org.uk

- Tweet

The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation is pleased to present Hikaru Fujii’s first solo exhibition in the UK, Lines, Gazes, Landscapes.

Fujii is one of Japan’s most prominent contemporary artists, primarily working with film to explore the role of artistic practice within today’s social and political conditions. His practice is grounded in extensive historical research and frequently draws on archival materials related to Japanese imperialism and colonial occupation. This exhibition brings together several works by Fujii, shown in the UK for the first time, to examine moments in which empire and disaster appear side by side, occupying the same space.

Southern Barbarian Screens (2017) reconstructs scenes of trade depicted in sixteenth-century Japanese paintings called Nanban Byōbu (Southern Barbarian Screens) which portray the arrival of Europeans in Japan at that time. It brings into view the systems of slavery and the asymmetries of the colonial gaze that were rendered invisible behind narratives of exchange with the West.

Playing Japanese (2017) documents a workshop by Fujii that reenacts the imperial gaze of the Japanese people in the early twentieth century. Reconstructing the social conditions surrounding the Pavilion of Human Races at the 1903 National Industrial Exhibition in Osaka, the work reflects on human displays influenced by Western precedents, which included people from Africa and Asia as well as populations colonised by Japan, such as Ainu, Okinawan, Taiwanese, and Korean peoples.*1 The work reveals how the idea of a homogeneous and superior Japanese race was constructed, and how this imperial gaze continues to persist in contemporary Japanese society.

Record of Coastal Landscape (2011, 2015) is a panoramic documentation of coastal areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake. The earthquake, devastating tsunami, and nuclear accident destroyed many of the lines drawn by humans – urban planning grids, sea walls, and land-use boundaries – exposing geological formations and topographies that had long been concealed. Rather than focusing on the traces of destruction themselves, the work presents the figure of the land that emerges in their aftermath.

A Classroom Divided by a Red Line (2021) is based on an exercise developed by American educator Jane Elliott in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Her approach emerged from a sense of urgency to address racism “in a concrete way, not just talk about it,” after years of discussion in the classroom.*2 Fujii adapts this exercise to a classroom context ten years after the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster, at a time when discrimination against people displaced from Fukushima remained widespread, fuelled by fears of invisible radiation and the spread of misinformation. The work visualises how humans, even as young as ten years old, draw lines, assign roles, and generate exclusion and discrimination.

What runs through all of these works is not a simple reenactment of past events or catastrophes nor an appeal to remembrance or moral judgement – a concern sharpened fifteen years after the Great East Japan Earthquake and eighty years after the end of World War II. Rather, they seek to inhabit ongoing struggles: forms of violence that are not confined to history but persist into the present. The works refuse the comfort of critical distance, exposing the position from which viewers themselves, as those who look and observe, become implicated in structures of power.

By questioning how the historically formed imperial gaze and disasters that continue to unfold in the present coexist and stand adjacent to one another, this exhibition probes the tension that binds them. Set against an era marked by large-scale catastrophes – genocidal wars, territorial expansion, rising authoritarianism, failing systems, nationalist rhetoric, and environmental collapse – Fujii’s practice asks us to reflect on our own roles in knowing and shaping history: what kinds of histories will be told in the future, who has the power to determine them, and whether we choose to remain passive observers of our time.

*1: Masashi Kohara, Imperial Festival: World Expositions and Human Exhibitions, SUISEISHA, 2022. Prior to the opening, objections were formally raised by the Qing dynasty, and as the matter risked developing into a diplomatic issue, the planned exhibition of Qing nationals was cancelled. Following the opening, further objections were submitted by the Korean Empire and by Okinawa, resulting in the removal of those respective displays.

*2: A Class Divided, first broadcast on FRONTLINE March 26, 1985 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/class-divided/

Text by Haruna Takeda

Southern Barbarian Screens, one of the works presented in this exhibition, is featured in an article in ArtReview and will be screened online from 15 January 2026.

About the contributor

Hikaru Fujii

Hikaru Fujii utilises diverse media, including installations, film, and workshops, to bridge art, history, and society. His practice is rooted in extensive research and fieldwork, often focusing on specific historical moments and social issues. Through his work, he critically examines contemporary and historical crises and structural violence, investigating their societal impact and significance. His work has been exhibited at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; M+; National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA); Centre Pompidou-Metz; Kadist (Paris); and Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin), among others. He has also participated in numerous international art festivals, including the Asia Pacific Triennial (2021) and the Rencontres d’Arles (2024).

Admission Free

Related events:

Private View: Lines, Gazes, Landscapes by Hikaru Fujii

Wednesday 4 March, 5pm-8pm

Artist Talk: Hikaru Fujii in Conversation with May Adadol Ingawanij

Wednesday 4 March, 6:00pm – 7:00pm