Spotlight on... Dr Rupert Faulkner, Senior Curator of Japanese Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum

2020/11/13

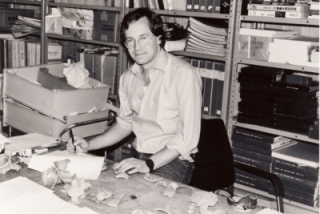

Dr Rupert Faulkner at the Idemitsu Museum, studying Koseto ware sherds, 1983

Dr Rupert Faulkner at the Idemitsu Museum, studying Koseto ware sherds, 1983

Dr Rupert Faulkner, Senior Curator of Japanese Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was awarded the The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays by the Japanese Government in the 2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals. In this month`s webmagazine, we turn our spotlight on Dr Faulkner for a special interview to talk about his career and achievements.

Tell us how you came to join the V&A.

I joined the V&A in September 1984. I had studied Japanese at Cambridge as an undergraduate and I did my doctorate, with a focus on Japanese ceramic history, at Oxford. While I was in Japan studying on a grant, I met people from the V&A who said that I should consider applying for a new position for a Japan curator that was coming up. That was the beginning.

What a remarkable period to be working at the V&A. You oversaw some substantial changes in both how the Japanese collection is organised and catalogued, and also how it is presented.

Yes, when I joined, the head of department, Joe Earle, had persuaded the then director of the V&A Sir Roy Strong that the gallery in which temporary exhibitions were held should become a full-scale Japanese gallery. That had been agreed before I joined, but the funding had not - and this was before corporate social responsibility that funds all sorts of projects today. The Toshiba Corporation came on board thanks to the then Ambassador Yamazaki, and the gallery opened at the end of 1986, two years after I joined.

Talk us through the process of selecting, from amongst the V&A’s substantial collection, the pieces that would be displayed in the newly opened gallery.

It basically involved going through the whole of the Japanese collection. Between Joe Earle, myself and three others we created lists that we gradually honed down. The basic design of the gallery, which remains unchanged today, is modular, so gives you the flexibility to change things around and experiment with different arrangements of objects. This flexibility has been a great strength of the gallery and has allowed us to create many different temporary displays over the years. To have been allocated 400 square meters in a run of ground floor spaces was quite something, and we have benefitted hugely from the gallery being in such a prime location.

It seems when you walk in these days, perhaps what you might expect to see is not necessarily what you do see, especially when you think about contemporary and manufactured objects. What do you see as the role of these objects in the Japanese story?

The configuration of displays we have now was put in place in 2015. Thanks to the Toshiba Corporation extending their naming of the gallery for another 10 years from 2011 we were able to undertake an upgrade of the gallery. We interviewed members of the public as well as museum colleagues and other specialists to see what people thought should be included in the gallery. In all cases ‘more of the contemporary’ was the main message. With this feedback we decided to broaden the scope of the displays to include examples of industrial and product design, of popular fashion, and also of photography. I was the Lead Curator for the refurbishment and upgrade, which took two and a half years to plan and deliver.

One of your areas of expertise is ukiyo-e, woodblock prints, can you tell us a little about your experiences with these artworks?

My background is actually in Japanese ceramic history but I was employed by Joe Earle to work on the V&A’s ukiyo-e woodblock print collection. As well as helping with the new gallery, I spent time going through the entire run of 25,000 prints and what had been published about them. In the course of this I became particularly interested in a small group of around 100 fan prints by Hiroshige, many of which were in wonderful condition. Some years later, in 1997 to be precise, when there was a Hiroshige exhibition at the Royal Academy, I was contacted by a group from the Ukiyo-e Society of America, who knew about the fan prints. When I showed these to them they were genuinely bowled over and said to me ‘you must do something about getting them published.’ And that is what I did, the result being a volume entitled Hiroshige Fan Prints (V&A Publications, 2001), which presented the entire collection for the first time. It was a really enjoyable project.

The Mazarin Chest is arguably one of the finest pieces of Japanese export lacquer to have survived to the present day. Can you tell us about the object, and the project to have it conserved that we understand you played a major role in?

I joined the V&A in September 1984. I had studied Japanese at Cambridge as an undergraduate and I did my doctorate, with a focus on Japanese ceramic history, at Oxford. While I was in Japan studying on a grant, I met people from the V&A who said that I should consider applying for a new position for a Japan curator that was coming up. That was the beginning.

What a remarkable period to be working at the V&A. You oversaw some substantial changes in both how the Japanese collection is organised and catalogued, and also how it is presented.

Yes, when I joined, the head of department, Joe Earle, had persuaded the then director of the V&A Sir Roy Strong that the gallery in which temporary exhibitions were held should become a full-scale Japanese gallery. That had been agreed before I joined, but the funding had not - and this was before corporate social responsibility that funds all sorts of projects today. The Toshiba Corporation came on board thanks to the then Ambassador Yamazaki, and the gallery opened at the end of 1986, two years after I joined.

Talk us through the process of selecting, from amongst the V&A’s substantial collection, the pieces that would be displayed in the newly opened gallery.

It basically involved going through the whole of the Japanese collection. Between Joe Earle, myself and three others we created lists that we gradually honed down. The basic design of the gallery, which remains unchanged today, is modular, so gives you the flexibility to change things around and experiment with different arrangements of objects. This flexibility has been a great strength of the gallery and has allowed us to create many different temporary displays over the years. To have been allocated 400 square meters in a run of ground floor spaces was quite something, and we have benefitted hugely from the gallery being in such a prime location.

It seems when you walk in these days, perhaps what you might expect to see is not necessarily what you do see, especially when you think about contemporary and manufactured objects. What do you see as the role of these objects in the Japanese story?

The configuration of displays we have now was put in place in 2015. Thanks to the Toshiba Corporation extending their naming of the gallery for another 10 years from 2011 we were able to undertake an upgrade of the gallery. We interviewed members of the public as well as museum colleagues and other specialists to see what people thought should be included in the gallery. In all cases ‘more of the contemporary’ was the main message. With this feedback we decided to broaden the scope of the displays to include examples of industrial and product design, of popular fashion, and also of photography. I was the Lead Curator for the refurbishment and upgrade, which took two and a half years to plan and deliver.

One of your areas of expertise is ukiyo-e, woodblock prints, can you tell us a little about your experiences with these artworks?

My background is actually in Japanese ceramic history but I was employed by Joe Earle to work on the V&A’s ukiyo-e woodblock print collection. As well as helping with the new gallery, I spent time going through the entire run of 25,000 prints and what had been published about them. In the course of this I became particularly interested in a small group of around 100 fan prints by Hiroshige, many of which were in wonderful condition. Some years later, in 1997 to be precise, when there was a Hiroshige exhibition at the Royal Academy, I was contacted by a group from the Ukiyo-e Society of America, who knew about the fan prints. When I showed these to them they were genuinely bowled over and said to me ‘you must do something about getting them published.’ And that is what I did, the result being a volume entitled Hiroshige Fan Prints (V&A Publications, 2001), which presented the entire collection for the first time. It was a really enjoyable project.

The Mazarin Chest is arguably one of the finest pieces of Japanese export lacquer to have survived to the present day. Can you tell us about the object, and the project to have it conserved that we understand you played a major role in?

The Mazarin Chest, 2015

The Mazarin Chest, 2015

The Mazarin Chest has long been recognised as one of the great examples of Japanese lacquer made for export to Europe in the early 17th century. We have other pieces of similar quality in the collection, but none of them as large. There are articles about the chest published in Japanese going back quite a while, and many years ago, long before my time, it once travelled to Japan. A certain amount of conservation work was done on the chest between it moving from a gloomy corridor space next to the Chinese gallery and going on display in the Toshiba Gallery in 1986. What triggered the Mazarin Chest Project (2003-2011) was the Japanese government’s programme for the conservation of Japanese treasures in overseas collections, in connection with which we received a visit by a research team looking for candidate objects to conserve in Japan. The upshot was that in about 2000 we received an invitation to send the Mazarin Chest to Tokyo. We thought it would be fantastic to have it conserved as we knew it was far from being in good condition. Our one concern, however, about sending the chest to Japan was that although it would have been put right, and we would have received detailed notes about what had been done to it, we would be little the wiser about how to best maintain the chest and the hundreds of other Japanese lacquer objects we have at the V&A. So we decided we wouldn’t take up the invitation to send the chest to Japan and would instead set up a team of curators and conservators with whom we would invite a specialist Japanese lacquer conservator to come and work. It was a very complicated and ambitious plan. I sometimes wonder why we ever embarked on it!

The project brought to the fore, as we had anticipated, major ethical or ideological differences between western and Japanese approaches to conservation. One of the key issues with lacquer objects is whether or not to do what is done in Japan, which is to use as far as possible the same materials, most importantly urushi lacquer, as were employed at the time of making. If you use urushi lacquer it can never be removed. This goes against a key principle of western conservation practice, which is that any treatment must be fully reversible. To employ urushi lacquer is to do something irreversible when potentially there could or should be other materials that might be used. Because of this there had always been, well battle is perhaps too strong a word, but ongoing contention between western and Japanese conservators of lacquer. We were very fortunate in this respect that the Japanese conservator we employed was not only extremely skilled but was also open to considering the use of non-traditional materials. With the scientific research conducted as part of the project and the experience we gained of using urushi for making sample boards for testing, we realised that our aim should not be reversibility but rather re-treatability. They sound like the same thing but are actually quite different. If something is re-treatable you are able to work again on an object using the same materials that were previously used to conserve it even if the treatment is irreversible. In order to inform and then justify the approach we adopted, scientific research was conducted by conservation scientists at the V&A and PhD students at Imperial College London, just across the road from the V&A, and other research institutes. The reports and papers in which this work resulted added very considerably to the English language literature about East Asian lacquer and the use of urushi as a conservation material.

Another side of the story was the art historical one. Funnily enough Joe Earle, whom I mentioned was head of department when I joined the V&A, had published in 1983 an important article about the Mazarin Chest and other very high quality Japanese export lacquer objects of the same period. At that stage it was known from photographs that there was a second similar looking chest whose whereabouts after the early 1940s was unknown. We also knew there was a third chest because we had lacquer panels resembling the front and sides of the Mazarin Chest that had been cut up and incorporated into a piece of French furniture we had in the V&A. Surprising though it sounds, it was common in the 18th century, especially in France, for Japanese lacquer screens and cabinets to be ‘cannibalised’ for incorporation into items of European furniture. We also found out thanks to research conducted by a Dutch scholar into the archives of the Dutch East India Company - the channel through which the Mazarin Chest and other pieces of Japanese lacquer came to Europe - that there had originally been four chests. So we concluded ‘we have photographs of one chest that has gone missing, we have the Mazarin Chest, we have parts of a third chest, and we know from documentary evidence that there must have been a fourth chest.’

The main results of the Mazarin Chest Project were published in 2011 in the proceedings of a conference held at the V&A two years earlier entitled Crossing Borders: The Conservation, Science and Material Culture of East Asian Lacquer. Not long after, in 2013, an auction house in France contacted us to say ‘we think we have found something very similar to your Mazarin Chest.’ To our utter amazement this turned out to be the missing chest in the photographs! It transpired that it had been bought in 1941 from the sale of the contents of Llantarnam Abbey in Wales by a collector who lived within a stone’s throw of the V&A. If only we had known! It then passed into the hands of a French engineer who retired to the Loire Valley in 1986, where he had apparently used it as a drinks cabinet and television stand. It was auctioned in June 2013 and purchased for over seven million Euros by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which of course could not have been a more appropriate place for it to have gone to.

This was all as exciting as it was extraordinary. But there was still more to come, for only months later a colleague in our metalwork department who had contacts in Russia received an email from someone she knew in the State Historical Museum in Moscow saying they had found an ‘object with very interesting metal fittings’ and asking whether the V&A could help identify them. As soon as the photographs arrived our colleague rang us in great excitement to say another Mazarin Chest lookalike seems to have turned up in Moscow. We just couldn’t believe it, but lo and behold, it was indeed the missing chest no. 4! It had been used for storing furs by a Russian aristocrat who gave it to the textile department of the State Historical Museum at the beginning of the 20th century. Once the furs had been removed, nobody knew what to do with the chest except to pack it into a large crate and push it into a corner. The crate remained unopened until somebody a hundred years later was sorting out the museum’s stores and wondered what was inside.

So all because of its fittings this object was rediscovered! Have the four chests ever been shown together?

At the moment it is impossible to think of doing anything as ambitious as that but yes, I think one day it would be splendid to organise a ‘returning to Japan’ tour of the four chests. In October 2015 the Rijksmuseum held an exhibition called Asia in Amsterdam that looked at the activities of the Dutch East India Company and the goods they brought back from Asia. Two of the centrepieces of the exhibition were the ‘television stand’ and the ‘fur chest’, which they managed to borrow from Moscow at quite short notice. We were unable to lend the Mazarin Chest because the exhibition coincided with the reopening of the Toshiba gallery. I would love to see all four – or three and a half – chests travel to Japan. It would be a huge success, no doubt about it. Because I won’t be at the V&A for that much longer, this will be for others to organise, but yes, it would be tremendous.

Could you tell us about your plans for after you retire in May 2021?

Well, I haven’t decided really. Some people have books they want to write and so on, but I don’t actually have anything specific in mind to be honest. What I do quite a lot of at home, and I work with my wife on this, is translating from Japanese into English, which can be a very valuable thing to do. I think it is recognised in Japan that one of the problems with dialogue in the humanities, though less so in the sciences, is the language barrier that prevents Japanese and non-Japanese people from communicating. There is so much work done in Japan in the humanities that is not known about elsewhere because it is in a language that few non-Japanese can understand. Translation is therefore very important. In the area of contemporary craft and design, where my wife and I do much of our work, Japanese practitioners who have ambitions to be understood and known about outside Japan realise that they have to have their catalogues and essays translated into English. I enjoy translating even if it can be quite hard going. You can do it in your own time and at your own pace, and it’s usually a worthwhile thing to do.

A video of the full interview, which is illustrated with images from throughout Dr Faulkner’s career, will be published on the Embassy of Japan’s YouTube and social media channels.

Please follow us for updates: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter.

The project brought to the fore, as we had anticipated, major ethical or ideological differences between western and Japanese approaches to conservation. One of the key issues with lacquer objects is whether or not to do what is done in Japan, which is to use as far as possible the same materials, most importantly urushi lacquer, as were employed at the time of making. If you use urushi lacquer it can never be removed. This goes against a key principle of western conservation practice, which is that any treatment must be fully reversible. To employ urushi lacquer is to do something irreversible when potentially there could or should be other materials that might be used. Because of this there had always been, well battle is perhaps too strong a word, but ongoing contention between western and Japanese conservators of lacquer. We were very fortunate in this respect that the Japanese conservator we employed was not only extremely skilled but was also open to considering the use of non-traditional materials. With the scientific research conducted as part of the project and the experience we gained of using urushi for making sample boards for testing, we realised that our aim should not be reversibility but rather re-treatability. They sound like the same thing but are actually quite different. If something is re-treatable you are able to work again on an object using the same materials that were previously used to conserve it even if the treatment is irreversible. In order to inform and then justify the approach we adopted, scientific research was conducted by conservation scientists at the V&A and PhD students at Imperial College London, just across the road from the V&A, and other research institutes. The reports and papers in which this work resulted added very considerably to the English language literature about East Asian lacquer and the use of urushi as a conservation material.

Another side of the story was the art historical one. Funnily enough Joe Earle, whom I mentioned was head of department when I joined the V&A, had published in 1983 an important article about the Mazarin Chest and other very high quality Japanese export lacquer objects of the same period. At that stage it was known from photographs that there was a second similar looking chest whose whereabouts after the early 1940s was unknown. We also knew there was a third chest because we had lacquer panels resembling the front and sides of the Mazarin Chest that had been cut up and incorporated into a piece of French furniture we had in the V&A. Surprising though it sounds, it was common in the 18th century, especially in France, for Japanese lacquer screens and cabinets to be ‘cannibalised’ for incorporation into items of European furniture. We also found out thanks to research conducted by a Dutch scholar into the archives of the Dutch East India Company - the channel through which the Mazarin Chest and other pieces of Japanese lacquer came to Europe - that there had originally been four chests. So we concluded ‘we have photographs of one chest that has gone missing, we have the Mazarin Chest, we have parts of a third chest, and we know from documentary evidence that there must have been a fourth chest.’

The main results of the Mazarin Chest Project were published in 2011 in the proceedings of a conference held at the V&A two years earlier entitled Crossing Borders: The Conservation, Science and Material Culture of East Asian Lacquer. Not long after, in 2013, an auction house in France contacted us to say ‘we think we have found something very similar to your Mazarin Chest.’ To our utter amazement this turned out to be the missing chest in the photographs! It transpired that it had been bought in 1941 from the sale of the contents of Llantarnam Abbey in Wales by a collector who lived within a stone’s throw of the V&A. If only we had known! It then passed into the hands of a French engineer who retired to the Loire Valley in 1986, where he had apparently used it as a drinks cabinet and television stand. It was auctioned in June 2013 and purchased for over seven million Euros by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which of course could not have been a more appropriate place for it to have gone to.

This was all as exciting as it was extraordinary. But there was still more to come, for only months later a colleague in our metalwork department who had contacts in Russia received an email from someone she knew in the State Historical Museum in Moscow saying they had found an ‘object with very interesting metal fittings’ and asking whether the V&A could help identify them. As soon as the photographs arrived our colleague rang us in great excitement to say another Mazarin Chest lookalike seems to have turned up in Moscow. We just couldn’t believe it, but lo and behold, it was indeed the missing chest no. 4! It had been used for storing furs by a Russian aristocrat who gave it to the textile department of the State Historical Museum at the beginning of the 20th century. Once the furs had been removed, nobody knew what to do with the chest except to pack it into a large crate and push it into a corner. The crate remained unopened until somebody a hundred years later was sorting out the museum’s stores and wondered what was inside.

So all because of its fittings this object was rediscovered! Have the four chests ever been shown together?

At the moment it is impossible to think of doing anything as ambitious as that but yes, I think one day it would be splendid to organise a ‘returning to Japan’ tour of the four chests. In October 2015 the Rijksmuseum held an exhibition called Asia in Amsterdam that looked at the activities of the Dutch East India Company and the goods they brought back from Asia. Two of the centrepieces of the exhibition were the ‘television stand’ and the ‘fur chest’, which they managed to borrow from Moscow at quite short notice. We were unable to lend the Mazarin Chest because the exhibition coincided with the reopening of the Toshiba gallery. I would love to see all four – or three and a half – chests travel to Japan. It would be a huge success, no doubt about it. Because I won’t be at the V&A for that much longer, this will be for others to organise, but yes, it would be tremendous.

Could you tell us about your plans for after you retire in May 2021?

Well, I haven’t decided really. Some people have books they want to write and so on, but I don’t actually have anything specific in mind to be honest. What I do quite a lot of at home, and I work with my wife on this, is translating from Japanese into English, which can be a very valuable thing to do. I think it is recognised in Japan that one of the problems with dialogue in the humanities, though less so in the sciences, is the language barrier that prevents Japanese and non-Japanese people from communicating. There is so much work done in Japan in the humanities that is not known about elsewhere because it is in a language that few non-Japanese can understand. Translation is therefore very important. In the area of contemporary craft and design, where my wife and I do much of our work, Japanese practitioners who have ambitions to be understood and known about outside Japan realise that they have to have their catalogues and essays translated into English. I enjoy translating even if it can be quite hard going. You can do it in your own time and at your own pace, and it’s usually a worthwhile thing to do.

A video of the full interview, which is illustrated with images from throughout Dr Faulkner’s career, will be published on the Embassy of Japan’s YouTube and social media channels.

Please follow us for updates: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter.