Spotlight on... Dr Robin Wilson, Director, Oxford University Kilns

2022/1/19

The current exhibition at the Embassy of Japan, ASH, EMBER, FLAME: a Japanese Kiln in Oxford is as much about the firing process as it is the pots themselves. The circumstances of the firing of the pots, and the kilns project itself, is a fascinating one. In this Spotlight on article, the Embassy spoke to the Director of the Oxford University Kilns, Dr Robin Wilson of Keble College, about his career and research, and how that brought him to fire these forms of Japanese kiln.

For more information about the exhibition and to book free tickets, please click here.

Can you tell us about your academic background?

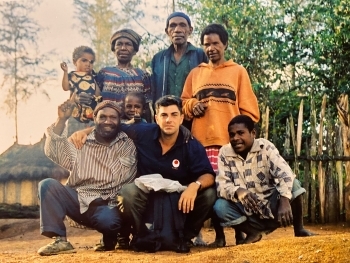

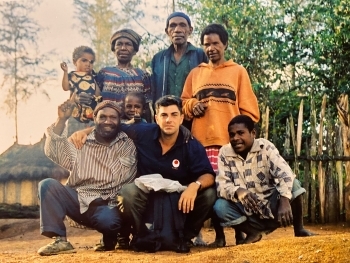

I work as an anthropologist at the University of Oxford’s Wytham Woods at present, but this wasn’t how I started my academic career. I have degrees in geology, geography and anthropology, and my doctorate is in geochemistry. I was working all over the Pacific and the Middle East on my doctorate – the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Oman, Cyprus and so on.

Although the research was all very interesting, it wasn’t leading me in a career direction I was happy with. One thing I took from that period that I really wanted to hang on to, however, was that the fieldwork based in the Pacific, in the Solomon Islands, in Fiji, and in New Guinea in particular. I also discovered a talent for acquiring languages and a real pleasure in talking to people.

I realised after some hesitation that I could potentially position myself in an anthropology rather than a geology department, spending my time talking to indigenous people in the Pacific about and around conflict resolution relating to large-scale mines, which I understand the operations of. I found that a good way to talk to people is to do it when you’re engaged in some kind of communal activity with them. Cooking works well, or helping dig sweet potatoes or arts and crafts. Participant observation is one of the defining methods of social anthropology, and one of its principal components is serendipity, which is essentially just letting things happen that are beyond your planning or control. It’s a great way to learn, and it’s really productive and helpful to meet people on their own terms in unthreatening and pleasant situations.

How do these early experiences tie in to what you have set up with the anagama kiln project in Oxford currently?

From the work I undertook in the Pacific - and I was working with local people there for a decade - I developed a very strong desire for a social agenda based on talking and making, creating things together and learning things from it. Ceramics and printmaking are my two main interests. The Kilns sit alongside a set of traditional printing presses and workshops I’ve also set up at Oxford as part of this extended investigation into learning by doing, which is often called Practice Based Research.

Anthropology is a political discipline to do with both looking at communities and people, but also creating, representing, understanding and learning things with them as much as it is learning things about them.

Tell us about the anagama kilns you have at the Oxford University Kilns.

We’ve built three single-chambered, wood-fired Japanese anagama kilns at the University of Oxford’s research woodlands at Wytham. The kilns are all different. Two large, one small. The largest is built of bricks that we brought over from Japan and the kiln itself was built by a kiln-builder called TAKIKAWA Takuma who was sent to us by the 5th Living National Treasure of Bizen, Okayama, Japan, ISEZAKI Jun, who was the first Patron of the Project. Takuma came to Oxford first as a Resident Artist in 2015 to build the large kiln, which is in fact an exact replica of his own kiln in Bizen. If you haven’t come across Bizen before, it's one of the so called ‘six mediaeval kilns’ of Japan, best known for unglazed stoneware, which reached its first apogee in the Momoyama Period - the late 1570’s to 1600, when Bizen-ware became popular in Cha-no-yu - Japanese tea ceremony.

The second kiln was built from measurements and examinations we made of ruined Kamakura-era kilns in the hills above the Bizen Valley. The shattered remnant of these old kilns show the dimensions and the construction methods sufficiently well to allow their reconstruction. Looking at shard-piles and ruined kilns is what allowed the potters of Bizen to recreate their own anagama kilns in the 1960s long after any fireable examples still remained. We did the same. Our middle-sized kiln was built around a tied basket-like former made of willow (in the absence of bamboo), over which we laid a thick daub of clay mixed with sand and other things. We built that kiln with a team of volunteers. It’s a large kiln, and takes nine or ten days to fire, as opposed to the twelve or more days of our largest kiln.

In 2017 I was successful in applications to the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation and the Sasakawa Foundation who between them paid for 50% of a new, smaller, test kiln. I raised the rest of the money myself from various donors and events, and all together I had enough to invite Takuma back again as Resident Artist at Oxford to build a relatively fast firing test kiln that could be used by more people more often, and to give more people the chance to learn how to use it. On visits to Bizen, Labourne (a ceramics village in France) and on site in Oxford I learned to fire and lead firings myself of this type of the kiln. Having done so, for the past couple of years I have been able to guide new teams of potters into using and firing the anagamas at Oxford.

Although the project doesn't seek to recreate a Japanese pottery, there is naturally a strong Japanese influence on the project via the connection with Bizen. Can you tell us a little more about that?

If you look in the Bizen Pottery Museum in Okayama you will see that the previous four Living National Treasures were producing very traditional looking forms. That is not the case with the 5th Living National Treasure! Although he is clearly rooted in tradition, he is also bringing lots of new ideas to the fore. I think that is why he sent us his kiln-builder and sent out several young potters from the Bizen area to help kick-start the project. ISHIDA Kazuya was one of these. I created a University Artists Residency for him at Linacre College, Oxford from which he came and helped Takuma fire the kilns, but also started to exhibit, develop his own contacts and practice, and create his own career.

There is also a recognition that there is an over-saturation in some respects of traditional kilns and potters in Japan, which I experienced when working in Bizen. Many of the young potters - fantastic potters who perhaps didn’t have the family history of potting, who are working at these ancient kilns sites, find themselves having to take up supplementary employment alongside their potting despite their skill. ISEZAKI Jun, because of his character, can see these problems, which are bordering on crisis, and to my mind, he seems to be encouraging young potters to get out there and learn things, do things, in the world outside of Japan. Likewise he discourages them replicating his work, and encourages them finding their own voice. The encouragement from the Japanese side is what helped me get the ball rolling with the kilns at Oxford.

There is also a recognition that there is an over-saturation in some respects of traditional kilns and potters in Japan, which I experienced when working in Bizen. Many of the young potters - fantastic potters who perhaps didn’t have the family history of potting, who are working at these ancient kilns sites, find themselves having to take up supplementary employment alongside their potting despite their skill. ISEZAKI Jun, because of his character, can see these problems, which are bordering on crisis, and to my mind, he seems to be encouraging young potters to get out there and learn things, do things, in the world outside of Japan. Likewise he discourages them replicating his work, and encourages them finding their own voice. The encouragement from the Japanese side is what helped me get the ball rolling with the kilns at Oxford.

What is important is that this is not a living history project. My view is that if we, and potters in general, continue to do what we did 30 years ago, we are unlikely to succeed 30 years from now (outside of a few very specialist potteries and potters). At the Oxford University Kilns we don’t keep our firing methods secret and the process of learning is not linear. We left people learn for themselves to a certain extent. New ideas and groups emerge, diverge and reconnect over time to re-share ideas and grow. In that way, I am hoping that by creating a communal ceramics endeavour (and in that way it differs from almost all of the existing contemporary large wood-fired kilns in Japan) - it is a living tradition that can grow, rather than an ossified emulative reproduction of Japanese historical practices. That strongly reflects both Jun's and my own approach, where we have to find a living way to be makers and artists such that we can make our way forward through what we create.

You fire the kilns with the teams most of the time. Why is this your approach and what have you learnt?

The principle methodology of anthropology is participant observation, which is different from observation, which would be setting up kilns and just watching what the potters all do, by doing which I would of course learn some things. But what if you still do all of the observation but you yourself are also a kiln-firer? The range of things you would learn are completely different. You are not just leaning from doing, you are also impacting and shaping the direction of travel by your own participation. This introduces a moral component as it empowers the creation of a lovely society or a rather undesirable one. What the kilns are is a real world kiln site which continues to work as long as people continue to find value in it themselves. Not because I find value in it as a researcher, or because I have an interest in recreating pseudo-Japanese artefacts for a museum. If that were the case, I wouldn’t continue with the project.

There are three kilns at the site, why is this?

Part of what I wanted to do was create neutral space. In some respects if you want to do something new you need somewhere new to do it, and people do not come to fire these kilns to be judged. This is done so that people are free to make mistakes, and by making those mistakes you can learn faster. That is one of the great things about the smaller kiln, which we fired for ASH, EMBER, FLAME, as with the big kilns the process is not fast enough, and we cannot fire them often enough. This means that people have less opportunity to make mistakes and so the learning process is much slower. I would much rather people make mistakes quickly, and learn from them, and then not have to wait an entire year to fire again - which would be the case with the big kilns. As we can fire the smallest kiln twice a month or so, it means the gap between firing the kiln is small enough that mistakes are fresh in the firing team's memory, and they won't make them again; so they get better at firing and acquire skills which are scalable to the larger kilns.

The three kilns let us play up and down the scale, so to speak: quick firings, long firings, big teams, small teams. That flexibility is one of the great strengths of the project.

What are the overall aims of the project?

The thing with the kilns is there is no monolithic aim or endpoint for the project, which means it is free to grow and expand organically. This model is in a sense unusual, especially from an academic point of view. Looking at the way academic models often work, with a focus on qualitative data, this project is not founded on those terms and so it is often difficult, from an academic point of view, to understand it. The questions that arise do so naturally from the practice of firing the kilns, rather than the other way around. The questions arise from the society of potters rather than the other way around. I’m not creating a society of potters to answer pre-existing questions in my head.

The thing with the kilns is there is no monolithic aim or endpoint for the project, which means it is free to grow and expand organically. This model is in a sense unusual, especially from an academic point of view. Looking at the way academic models often work, with a focus on qualitative data, this project is not founded on those terms and so it is often difficult, from an academic point of view, to understand it. The questions that arise do so naturally from the practice of firing the kilns, rather than the other way around. The questions arise from the society of potters rather than the other way around. I’m not creating a society of potters to answer pre-existing questions in my head.

That said, it is unusual for anthropological research to create something as elaborate as a functioning kiln site. As an academic, it would be more common to go off somewhere, study a group of some sort, and then return to the office to write about it. I personally find that model restrictive. When I think about my experiences in the Pacific I was an insider-outsider, I still had my own world to return to and I was a less convincing insider than I am at my own kiln site firing kilns at least as well or better than most of the potters who fire alongside me.

So for that reason the success of this project matters because it is a part of me, it's not something I am studying or rather 'just' studying; I am part of it, I am invested in it just as much as the people who come to fire the kilns. So although the model is difficult to understand from an institutional point of view, it is a great model to have a sustained research project that is not contingent on the usual funding cycles. There are of course other Japanese kilns like this outside of Japan, but the added aspect of research, study and documentation outside of a practical ceramics course situation (and that is all too rare too) is unique to Oxford, and to my knowledge does not exist elsewhere.

For more information about the exhibition and to book free tickets, please click here.

Can you tell us about your academic background?

I work as an anthropologist at the University of Oxford’s Wytham Woods at present, but this wasn’t how I started my academic career. I have degrees in geology, geography and anthropology, and my doctorate is in geochemistry. I was working all over the Pacific and the Middle East on my doctorate – the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Oman, Cyprus and so on.

Although the research was all very interesting, it wasn’t leading me in a career direction I was happy with. One thing I took from that period that I really wanted to hang on to, however, was that the fieldwork based in the Pacific, in the Solomon Islands, in Fiji, and in New Guinea in particular. I also discovered a talent for acquiring languages and a real pleasure in talking to people.

I realised after some hesitation that I could potentially position myself in an anthropology rather than a geology department, spending my time talking to indigenous people in the Pacific about and around conflict resolution relating to large-scale mines, which I understand the operations of. I found that a good way to talk to people is to do it when you’re engaged in some kind of communal activity with them. Cooking works well, or helping dig sweet potatoes or arts and crafts. Participant observation is one of the defining methods of social anthropology, and one of its principal components is serendipity, which is essentially just letting things happen that are beyond your planning or control. It’s a great way to learn, and it’s really productive and helpful to meet people on their own terms in unthreatening and pleasant situations.

How do these early experiences tie in to what you have set up with the anagama kiln project in Oxford currently?

From the work I undertook in the Pacific - and I was working with local people there for a decade - I developed a very strong desire for a social agenda based on talking and making, creating things together and learning things from it. Ceramics and printmaking are my two main interests. The Kilns sit alongside a set of traditional printing presses and workshops I’ve also set up at Oxford as part of this extended investigation into learning by doing, which is often called Practice Based Research.

Anthropology is a political discipline to do with both looking at communities and people, but also creating, representing, understanding and learning things with them as much as it is learning things about them.

Tell us about the anagama kilns you have at the Oxford University Kilns.

We’ve built three single-chambered, wood-fired Japanese anagama kilns at the University of Oxford’s research woodlands at Wytham. The kilns are all different. Two large, one small. The largest is built of bricks that we brought over from Japan and the kiln itself was built by a kiln-builder called TAKIKAWA Takuma who was sent to us by the 5th Living National Treasure of Bizen, Okayama, Japan, ISEZAKI Jun, who was the first Patron of the Project. Takuma came to Oxford first as a Resident Artist in 2015 to build the large kiln, which is in fact an exact replica of his own kiln in Bizen. If you haven’t come across Bizen before, it's one of the so called ‘six mediaeval kilns’ of Japan, best known for unglazed stoneware, which reached its first apogee in the Momoyama Period - the late 1570’s to 1600, when Bizen-ware became popular in Cha-no-yu - Japanese tea ceremony.

The second kiln was built from measurements and examinations we made of ruined Kamakura-era kilns in the hills above the Bizen Valley. The shattered remnant of these old kilns show the dimensions and the construction methods sufficiently well to allow their reconstruction. Looking at shard-piles and ruined kilns is what allowed the potters of Bizen to recreate their own anagama kilns in the 1960s long after any fireable examples still remained. We did the same. Our middle-sized kiln was built around a tied basket-like former made of willow (in the absence of bamboo), over which we laid a thick daub of clay mixed with sand and other things. We built that kiln with a team of volunteers. It’s a large kiln, and takes nine or ten days to fire, as opposed to the twelve or more days of our largest kiln.

In 2017 I was successful in applications to the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation and the Sasakawa Foundation who between them paid for 50% of a new, smaller, test kiln. I raised the rest of the money myself from various donors and events, and all together I had enough to invite Takuma back again as Resident Artist at Oxford to build a relatively fast firing test kiln that could be used by more people more often, and to give more people the chance to learn how to use it. On visits to Bizen, Labourne (a ceramics village in France) and on site in Oxford I learned to fire and lead firings myself of this type of the kiln. Having done so, for the past couple of years I have been able to guide new teams of potters into using and firing the anagamas at Oxford.

Although the project doesn't seek to recreate a Japanese pottery, there is naturally a strong Japanese influence on the project via the connection with Bizen. Can you tell us a little more about that?

If you look in the Bizen Pottery Museum in Okayama you will see that the previous four Living National Treasures were producing very traditional looking forms. That is not the case with the 5th Living National Treasure! Although he is clearly rooted in tradition, he is also bringing lots of new ideas to the fore. I think that is why he sent us his kiln-builder and sent out several young potters from the Bizen area to help kick-start the project. ISHIDA Kazuya was one of these. I created a University Artists Residency for him at Linacre College, Oxford from which he came and helped Takuma fire the kilns, but also started to exhibit, develop his own contacts and practice, and create his own career.

There is also a recognition that there is an over-saturation in some respects of traditional kilns and potters in Japan, which I experienced when working in Bizen. Many of the young potters - fantastic potters who perhaps didn’t have the family history of potting, who are working at these ancient kilns sites, find themselves having to take up supplementary employment alongside their potting despite their skill. ISEZAKI Jun, because of his character, can see these problems, which are bordering on crisis, and to my mind, he seems to be encouraging young potters to get out there and learn things, do things, in the world outside of Japan. Likewise he discourages them replicating his work, and encourages them finding their own voice. The encouragement from the Japanese side is what helped me get the ball rolling with the kilns at Oxford.

There is also a recognition that there is an over-saturation in some respects of traditional kilns and potters in Japan, which I experienced when working in Bizen. Many of the young potters - fantastic potters who perhaps didn’t have the family history of potting, who are working at these ancient kilns sites, find themselves having to take up supplementary employment alongside their potting despite their skill. ISEZAKI Jun, because of his character, can see these problems, which are bordering on crisis, and to my mind, he seems to be encouraging young potters to get out there and learn things, do things, in the world outside of Japan. Likewise he discourages them replicating his work, and encourages them finding their own voice. The encouragement from the Japanese side is what helped me get the ball rolling with the kilns at Oxford.What is important is that this is not a living history project. My view is that if we, and potters in general, continue to do what we did 30 years ago, we are unlikely to succeed 30 years from now (outside of a few very specialist potteries and potters). At the Oxford University Kilns we don’t keep our firing methods secret and the process of learning is not linear. We left people learn for themselves to a certain extent. New ideas and groups emerge, diverge and reconnect over time to re-share ideas and grow. In that way, I am hoping that by creating a communal ceramics endeavour (and in that way it differs from almost all of the existing contemporary large wood-fired kilns in Japan) - it is a living tradition that can grow, rather than an ossified emulative reproduction of Japanese historical practices. That strongly reflects both Jun's and my own approach, where we have to find a living way to be makers and artists such that we can make our way forward through what we create.

You fire the kilns with the teams most of the time. Why is this your approach and what have you learnt?

The principle methodology of anthropology is participant observation, which is different from observation, which would be setting up kilns and just watching what the potters all do, by doing which I would of course learn some things. But what if you still do all of the observation but you yourself are also a kiln-firer? The range of things you would learn are completely different. You are not just leaning from doing, you are also impacting and shaping the direction of travel by your own participation. This introduces a moral component as it empowers the creation of a lovely society or a rather undesirable one. What the kilns are is a real world kiln site which continues to work as long as people continue to find value in it themselves. Not because I find value in it as a researcher, or because I have an interest in recreating pseudo-Japanese artefacts for a museum. If that were the case, I wouldn’t continue with the project.

There are three kilns at the site, why is this?

Part of what I wanted to do was create neutral space. In some respects if you want to do something new you need somewhere new to do it, and people do not come to fire these kilns to be judged. This is done so that people are free to make mistakes, and by making those mistakes you can learn faster. That is one of the great things about the smaller kiln, which we fired for ASH, EMBER, FLAME, as with the big kilns the process is not fast enough, and we cannot fire them often enough. This means that people have less opportunity to make mistakes and so the learning process is much slower. I would much rather people make mistakes quickly, and learn from them, and then not have to wait an entire year to fire again - which would be the case with the big kilns. As we can fire the smallest kiln twice a month or so, it means the gap between firing the kiln is small enough that mistakes are fresh in the firing team's memory, and they won't make them again; so they get better at firing and acquire skills which are scalable to the larger kilns.

The three kilns let us play up and down the scale, so to speak: quick firings, long firings, big teams, small teams. That flexibility is one of the great strengths of the project.

What are the overall aims of the project?

The thing with the kilns is there is no monolithic aim or endpoint for the project, which means it is free to grow and expand organically. This model is in a sense unusual, especially from an academic point of view. Looking at the way academic models often work, with a focus on qualitative data, this project is not founded on those terms and so it is often difficult, from an academic point of view, to understand it. The questions that arise do so naturally from the practice of firing the kilns, rather than the other way around. The questions arise from the society of potters rather than the other way around. I’m not creating a society of potters to answer pre-existing questions in my head.

The thing with the kilns is there is no monolithic aim or endpoint for the project, which means it is free to grow and expand organically. This model is in a sense unusual, especially from an academic point of view. Looking at the way academic models often work, with a focus on qualitative data, this project is not founded on those terms and so it is often difficult, from an academic point of view, to understand it. The questions that arise do so naturally from the practice of firing the kilns, rather than the other way around. The questions arise from the society of potters rather than the other way around. I’m not creating a society of potters to answer pre-existing questions in my head. That said, it is unusual for anthropological research to create something as elaborate as a functioning kiln site. As an academic, it would be more common to go off somewhere, study a group of some sort, and then return to the office to write about it. I personally find that model restrictive. When I think about my experiences in the Pacific I was an insider-outsider, I still had my own world to return to and I was a less convincing insider than I am at my own kiln site firing kilns at least as well or better than most of the potters who fire alongside me.

So for that reason the success of this project matters because it is a part of me, it's not something I am studying or rather 'just' studying; I am part of it, I am invested in it just as much as the people who come to fire the kilns. So although the model is difficult to understand from an institutional point of view, it is a great model to have a sustained research project that is not contingent on the usual funding cycles. There are of course other Japanese kilns like this outside of Japan, but the added aspect of research, study and documentation outside of a practical ceramics course situation (and that is all too rare too) is unique to Oxford, and to my knowledge does not exist elsewhere.